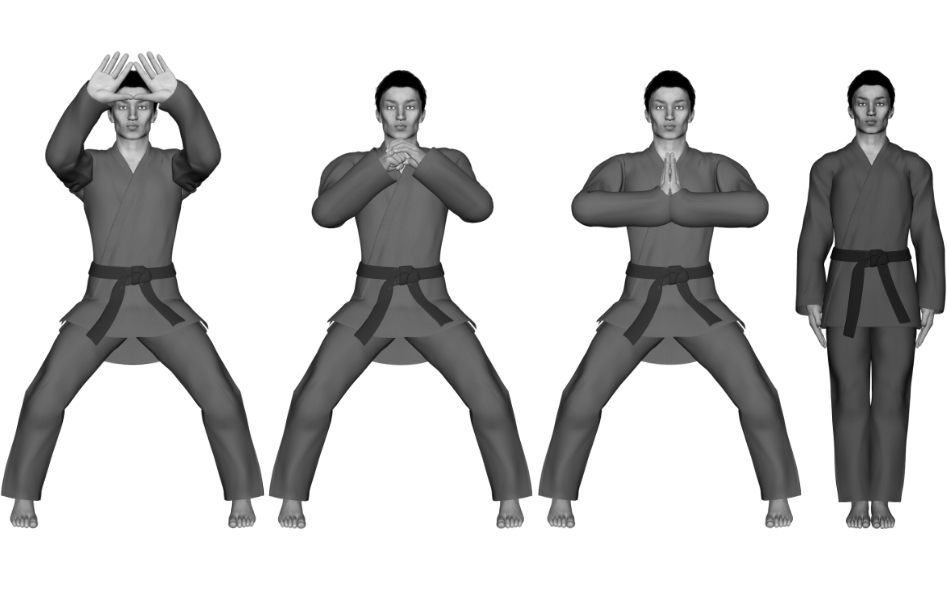

The original gestures that we now use as the first half of the full salutation in American Kenpo dates back further than one might suspect. This early salutation can be traced all the way back to the boxer rebellion in China. At that time, the salutation was used as a gesture to demonstrate that one was fighting to bring back the Ming dynasty; with the left hand over right fist representing the sun and the moon. In Chinese (Mandarin), these two characters combined represented the symbol of the Ming dynasty. The emperor of both the sun and the moon. Essentially, the emperor everything.

Rather that completely drop the original salutation, SGM Parker decided to maintain an homage to the past and build upon it, just as American Kenpo is built upon its past roots. This change was to denote a continuation of the modern martial arts from those of the past. These new motions were appended to end of the original gestures, to keep them fully intact and to demonstrate the modern progressing from the past. This combined series of movements is what modern American Kenpoists call their salutation.

Beginning with Short Form Three, each form starts their execution from an attention stance, rather than a horse stance. Therefore, the salutation for each of these higher forms is executed completely through to the closing attention stance, at which point the form begins.

One thing to note about the salutation as compared to the signification, in relation to the execution of a form, is that the salutation is always appended to both the beginning and the end of the form, where the signing gesture is only displayed at the beginning of the form. If one where to stop and think about this for a moment, it makes sense to only demonstrate the signification at the beginning of the form, but one might question why the salutation is also executed at the end of the form. This tradition starts to become apparent with the execution of Form Four.

The higher forms, starting with Form Four, integrate portions of the salutation into the form itself. The reasoning for this is to demonstrate that all motion has meaning within American Kenpo, and that even that salutation has application. Form Four accomplishes this at the very end of the form.

But where else is the salutation used, and why. There are a number of circumstances where the salutation is required in the system, such as: the opening and closing of classes, seminars, tests and other formal functions, and a modified salutation is generally use when greeting an instructor, another highly ranked practitioner, or simply another practitioner.

Most commonly, the full salutation is used in opening and closing formal functions, but can sometimes be shortened to just an opening and closing meditating horse - depending upon the instructor in charge. Usually, the more private the situation, the more likely the salutation is shortened or maybe even omitted. This depends mostly upon familiarity and strictness of the instructor than other aspects. But typically, the more public the situation, the more likely one is to encounter the full salutation being used.

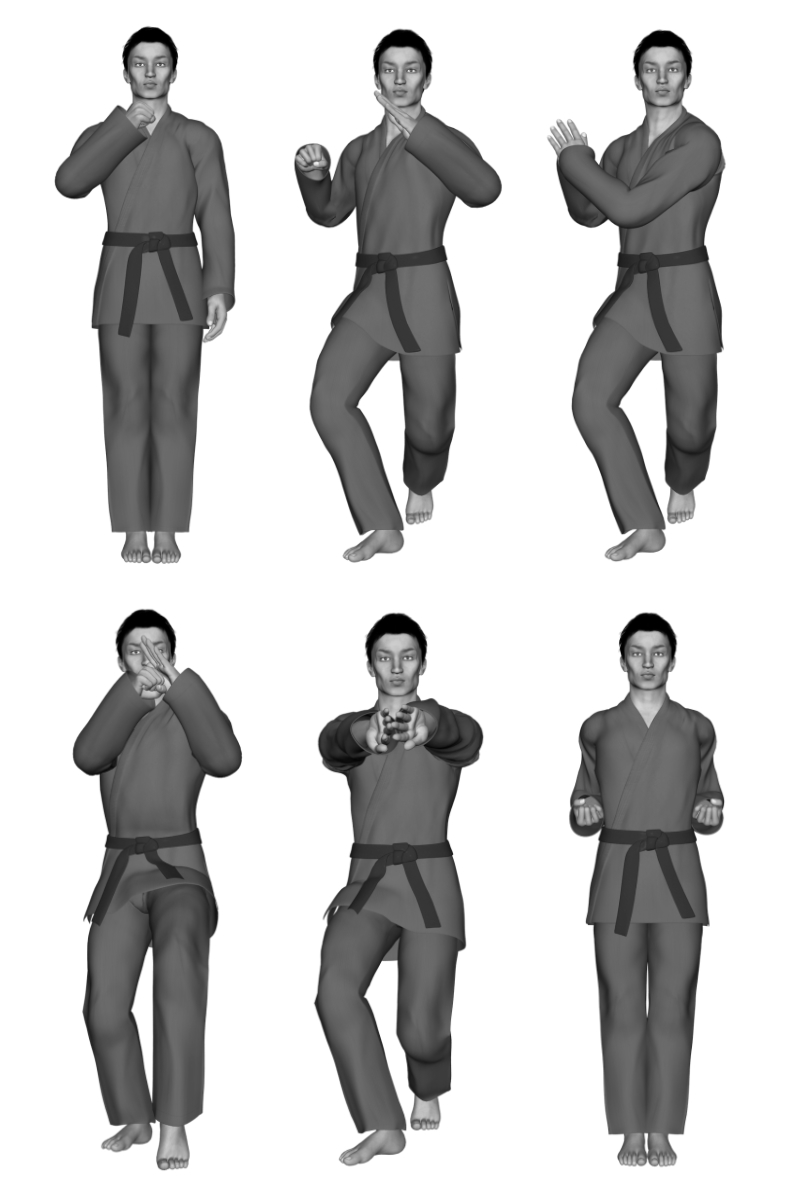

Greeting an instructor or high ranked practitioner is almost always reduced to the "left over right" hand gesture of the salutation (and often with the left cat stance of the salutation). Rarely is the full salutation executed in this situation. And, as time passes, the likelihood of the full salutation being executed in this situation becomes less and less.

American Kenpoists never bow to anyone - we only salute them. We bow only to inanimate objects or the conceptual. This is due to Americans being raised under the understanding that all people are created equal. And, historically speaking, bowing is a form of lowering one's self in deference to another. A salute, in contrast, is a show of respect. Another way of thinking about this is: salutes are military in origin and show respect, bowing is cultural in origin and show hierarchy.

In direct relationship to form execution, the salutation and signification combined together are intended to remove any ambiguity about the execution of the form. These gestures allow the viewer to not only determine the martial art style of the practitioner, which form is being performed, and whether the form will be modified from its standard execution or not - all without having to utter a word.

As mentioned above, the salutation and signifying are formal structures and are not often executed when an individual practices a form on their own, or even in class. In fact, it is uncommon for practitioners to execute the entire salutation and sign during practice sessions, unless they are simulating a test / tournament situation. This does not mean that the salutation and signing of a form should be overlooked as not important to the execution of the form. But rather, that the salutation and signifying add respect, formality, clarity, and uniformity for others.

One major difference that this guide has when compared to the all of the previous books in this series is that the salutation and signification are portrayed with the main form illustrations, rather than broken out into a separate subsection. This is a subtle acknowledgment to the fact that these gestures are intended to be integrated into the form itself.