Most Kenpoists are familiar with the Clock Principle and its usefulness in determining directionality. It is a very competent and basic principle for this purpose. But, what most Kenpoists are not aware of are its downsides.

First, where the principle is very good for two (2) dimensional directionalities, it is not very good for three (3) dimensions. To somewhat fix this, one must add another clock; typically, a vertical clock. But even that has a problem, because one must decide whether the face of the clock is facing to their left or their right. Plus, everyone must agree on this decision. And, in order to 'fix' for three (3) dimensions, a layer of complexity is also added.

Second, with the advent of the digital era, many people in modern generations can no longer read an analog clock, and therefore would not understand the reference to the phrase; "coming from your 7:30". So, to be referred to in a more precise manner for this modern age, the Clock Principle should really be called the Analog Clock Principle.

Also, going back to our previous example: even if the person did understand the directional reference and was able to determine the incoming direction, there is still another issue. Was the threat coming toward them coming on a straight forward path, on an upward trajectory, or a downward trajectory? This detail makes a big difference to any response.

To solve for these drawbacks, it was determined that a new principle might need to be created. A principle that was very easy to understand, easy to teach, would stand the test of time, and possibly be used in conjunction with the Analog Clock Principle. This principle would also have to be very easily adopted and not require any real special or external training. This quest resulted in the creation of the Directional Zone Principle - or Zone Principle for short.

Describing the Basic Directional Zone Principle

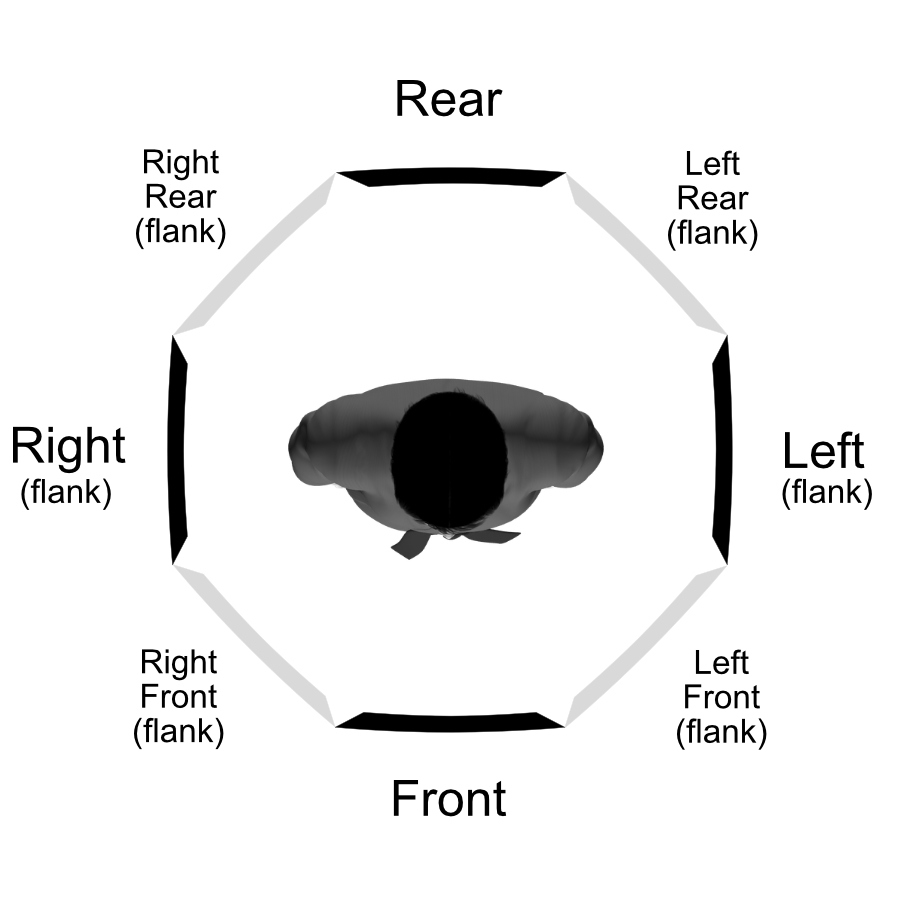

One of the key factors of the Zone Principle is that it maintains the same eight (8) horizontal primary directions as contained in the Clock Principle. The major difference is that each of these zones is given a logical name instead of a position on the clock. And, just like the Clock Principle it is divided into primary and secondary zones. The primary zones being: Front, Rear, Left, and Right. And, the secondary zones being: Right Front, Left Front, Left Rear, Right Rear.

Horizontal Zones View

3rd person perspective

(from top)

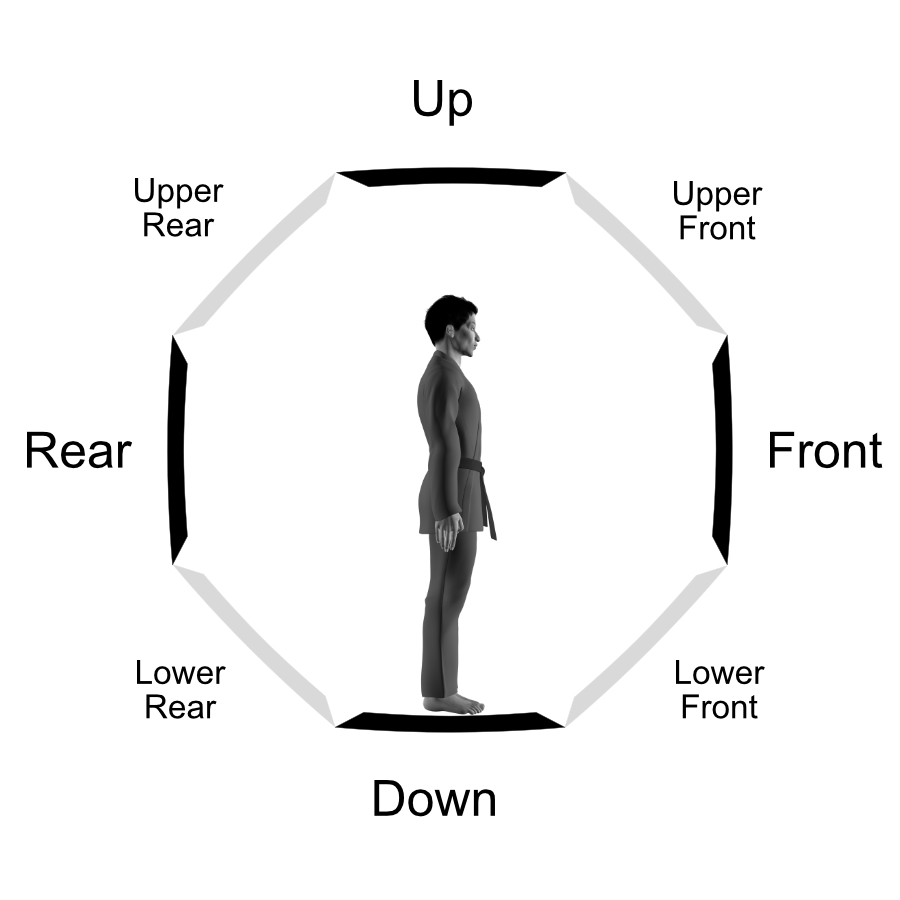

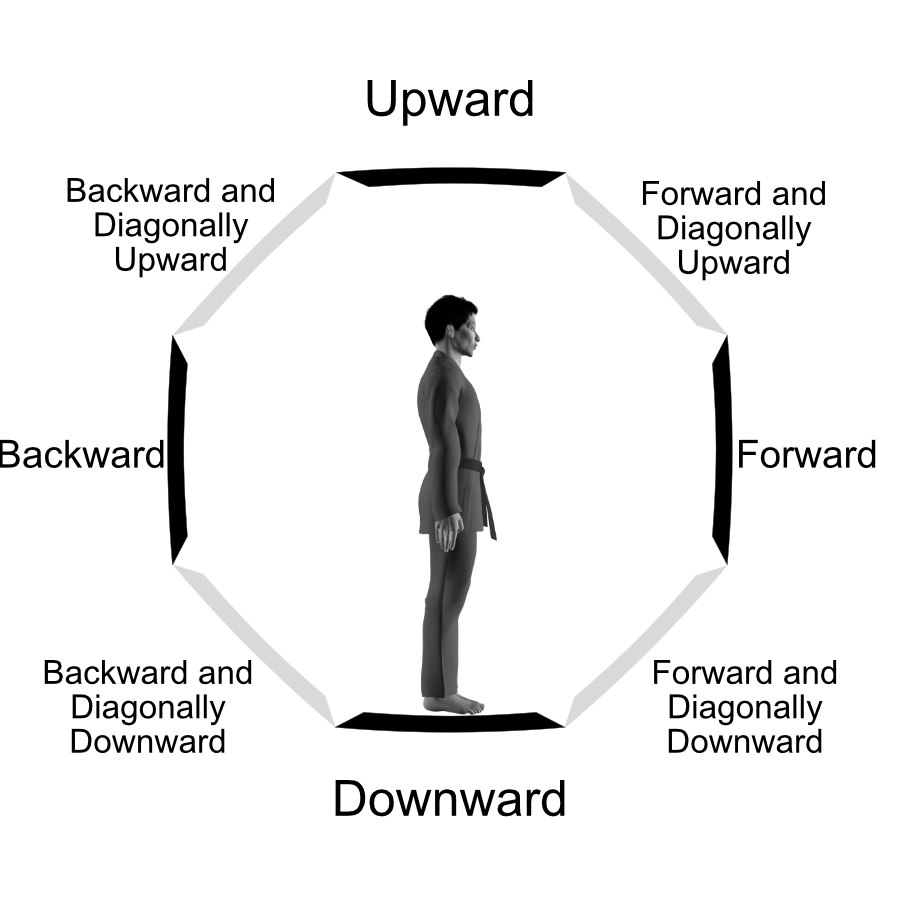

Also, a vertical dimension is added with the same eight (8) zones as the horizontal; with the same primary and secondary zone pattern as the horizontal version. The primary zones being: Front, Rear, Up, Down. And, the secondary zones being: Upper Front, Lower Front, Lower Rear, Upper Rear.

Vertical Zones View

3rd person perspective

(from right flank)

Combining these two planes together into a single signifier, one can describe all three (3) dimensions easily and effectively. For example, using the same example from earlier: "from your Left Rear" is just as easy to understand as: "from your 7:30". Or, even easier if you can't read an analog clock. And, using fewer total syllables - therefore quicker to say.

Furthermore, to add the third dimension, all one needs to do is add the descriptor from the vertical plane: "from your Upper Left Rear". Or, if one wishes to also integrate this into the Clock Principle: "from your Upper 7:30".

Even though only a single example was given, the reader can easily extrapolate all the remaining zones three (3) dimensionally around the body and come to a simple descriptor for each zone.

Directional Zone Details

Now that a general description of the principle is provided, another detail about this principle needs to be delved into. Why zones? Again, compared to the Clock Principle the Zone Principle more accurately describes reality. This is because the Clock Principle only describes a single point in space, where the Zone Principle describes a region of space.

This is important because even though an incoming attack may be directly from the front, what if it is slightly off of that point. Is it treated the same or differently? We know that at 45-degrees (Right Front or Left Front) that it is; but what about less than that? Where is the cut-off point? The Directional Zone Principle answers all these questions.

If one is to examine the diagrams above, they will soon realize that each zone covers a total zone of 45-degrees, with a 22.5-degree span on either side of the central focal point. This correctly implies that the entire 45-degree zone is treated the same. Also, it implies that the cut-off point for each zone is 22.5-degrees off center. Anything beyond that point falls into a different zone and will be treated differently - from both a responsive and directional perspective. And, this also holds true for the vertical zones.

Directional Zone Nomenclature

Like the name Directional Zone Principle being colloquially called the Zone Principle, there are other nomenclature details that need to be called out when using this principle.

First, the term flank. The term flank refers to being from the side (or lateral). Because of this, one may wish to include it into the zone names. For example: one may refer to the zone "Left" as "Left Flank" instead. It would mean the same thing. As another example, one may describe a directional zone as: "Upper Left Front Flank" or "Upper Left Front". Again, they would mean the same thing.

Then there is the decision as to when to include "Upper" or "Lower". Generally speaking, saying: "Front" or "Rear" implies from straight ahead or behind, respectively. In other words, not from an upper or lower direction. This holds true for all horizontal directional zones. It is only when one wants to include the vertical (third) dimension that using those terms is necessary. For example: "Front" and "Upper Front" refers to two completely different directional zones in three (3) dimensions, but refers to the same general direction horizontally.

Finally, there is alternative nomenclature that one may employ instead of "Upper" and "Lower". This would be: "High" and "Low". And, if one wishes to be even more specific in detail, they may use "Level" to refer to the horizontal directional zones. Using the example from the previous paragraph: "Level Front" and "High Front" would be the equivalent alternative.

This nomenclature might be more familiar to fighter pilots, which tend to use this alternate nomenclature in reference to orientation relative to a plane which is flying. And, although this nomenclature is a perfectly acceptable alternative to the one provided here, it is not used within these guides.

Local vs Global Perspectives

There is one more important detail that needs to be understood about this principle. It can be used in both a local and global perspective - each with their own nomenclature. But, what does that mean?

To understand this concept, one must first understand how to describe a complex illustration, like a form or a self-defense technique. As a form or self-defense technique progresses, directions may shift. For instance, if one illustrates the form Short Form One, one needs to determine how the directions of that form are conveyed to another person.

Decisions need to be made as to whether the written word describes the direction in which the practitioner is facing from the current point in the form (local), or whether the description is based upon a fixed orientation that is set at the beginning of the form (global).

For example: mentally proceed through Short Form One until after the execution of the first downward block. What direction is the practitioner facing? From a local (i.e. first person) perspective, the practitioner is facing the front. From a global (i.e. third person) perspective, the practitioner is facing the rear. How does one rectify this discrepancy in direction? Clearly, a solution must be sought out.

Fortunately, the Zone Principle solves for this dilemma. It does this by adding a local (i.e. first person) version of the principle that uses a similar, but distinct nomenclature.

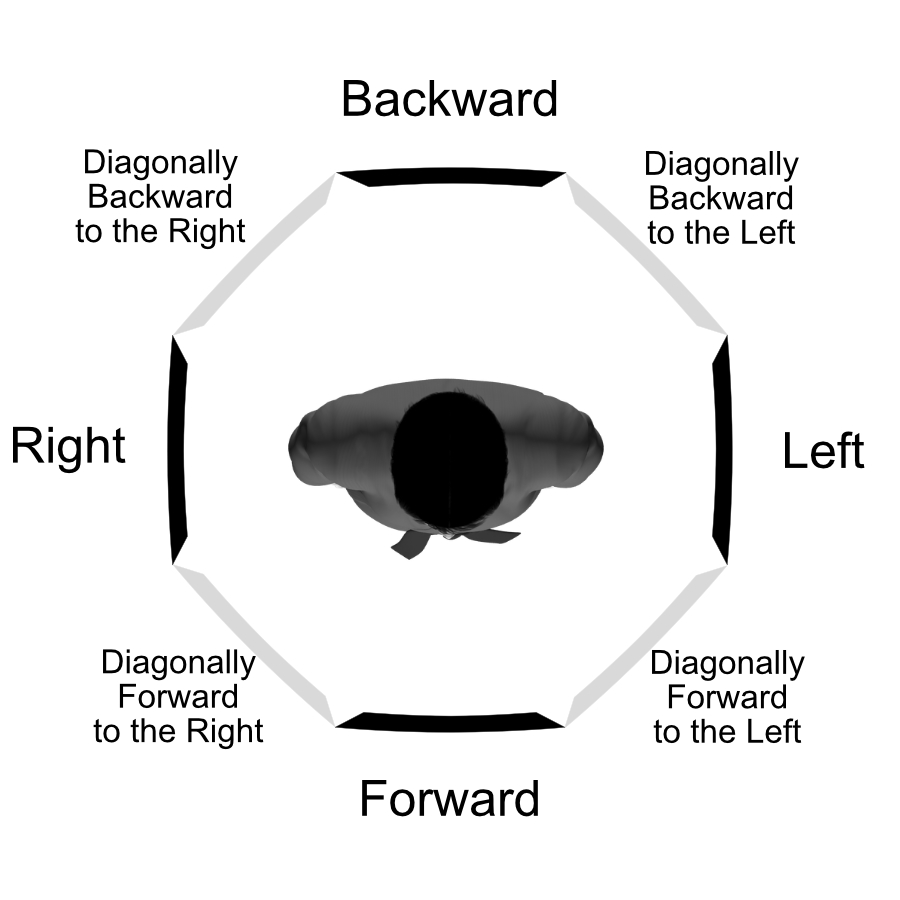

The horizontal version of the zones is called: Forward, Backward, Left, Right as the primary zones; and Diagonally for the secondary zones. For example: the zone "Diagonally Forward and to the Left" is easily understood. And to add the vertical dimension, the terms Upward and Downward are added to the zone descriptor. For example: "Forward and Diagonally Upward to the Left" is also easily understood.

One may argue that these are long descriptors. And, they would be correct. Luckily, these descriptors are not specifically designed to be used in speech. Rather, they are primarily designed to be used in written illustrations to explicitly describe directionality. And like there global counterparts, may also be used in conjunction with the Clock Principle. For example: to refer to the same zone as the example; one may say: "Diagonally Upward to 10:30" or "to 10:30 and Diagonally Upward".

Note: it is not a requirement that the terms be ordered exactly as the examples provided. But it is important that one use the distinct nomenclature between local and global descriptors. Otherwise, the reader/listener will not be able to easily determine which perspective is being referred to, unless further specified.

Also, this directionality equally applies to direction of step. For instance, one may state that the opponent steps backward or forward into a neutral bow stance. Or, covers left or right into a neural bow stance.

Horizontal Zones View - Local

3rd person perspective

(from top)

Vertical Zones View - Local

3rd person perspective

(from right flank)

One final peculiarity needs to be discussed about the different perspectives of direction within the Directional Zone Principle and how it relates to, but is different from Focus Point (A.K.A. Attention Point). Focus Point is where the attention of the practitioner is directed, rather than in which direction they are facing within a stance. In certain instances, although the practitioner's stance may be pointed toward a specific direction, it is not mandatory that their Focus Point be toward the same zone of direction. Even though it is most often the case that facing and focus point are the same, there are a great many instances where they are not.

For example, if one were to envision the last isolation sequence of Long Form Three, one can easily conclude that although the horse stance is facing forward, the attention shifts from the right side, to the left side, and then to both the left and right sides simultaneously as the sequence progresses - even though the stance never changes throughout the entire sequence. And, although this example is for an isolation sequence, in order to keep things simple, it is just as easily applied to a number of self-defense techniques and basics.

This important distinction is essential to understand and account for when learning to describe both the physically directed zone and the mental focus point in both a written and spoken illustration. Otherwise, the reader/listener will conclude that both are to the same zone of direction, since this is the most commonly occurring scenario. To specify this difference, one only need to call out the direction the stance is facing followed by a determination of which zone the Attention Point is focused.

For a local perspective example: step forward with your right foot into a right neutral bow stance facing forward with your attention directed diagonally forward and upward to your left.

For a global perspective example: step forward with your right foot into a right neutral bow stance facing the rear with your attention directed to the upper right rear flank.

Both of these examples are explicit as to which leg is being used, the direction of the step, which direction the stance faces, and to which direction the attention is placed. The difference is that the local example is more suited to a simple, single maneuver situation; where the global example is more suited to a more complex scenario, like in the middle of a self-defense technique or form. Regardless, both examples are succinct and presented in a way that is both easy to understand and fairly obvious when read. And, with very little practice easy to dictate or write.